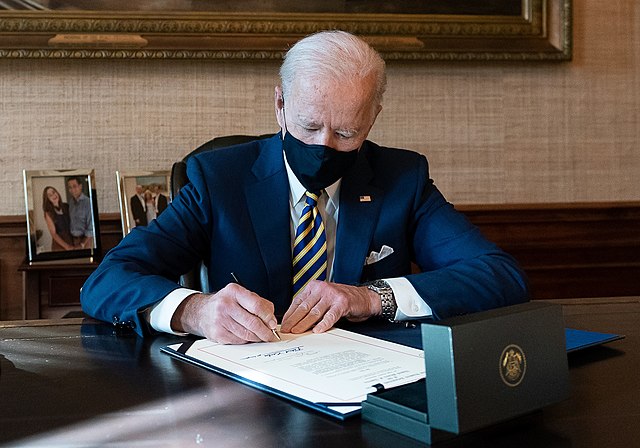

The newly inaugurated President Joe Biden has been busy during his first days in office. He has pledged to combat the coronavirus pandemic and put in place progressive priorities as quickly as he can, doing so through the use of various Executive actions. Many of President Biden’s Executive actions will directly undo those taken by former President Donald Trump. Others will not directly overturn previous orders but will set policies that are generally in opposition to those the former President pursued. Just hours after taking office, President Biden has already weakened Trump’s policy legacy. He did this all at the stroke of a pen—no Congress required.

“Executive actions” is a phrase that encompasses a variety tools that the President has at his disposal to put policies into place. Executive orders are the best-known of these tools, and others include Presidential memoranda, national security directives, proclamations, and signing statements. These various actions can have a wide array of effects. Some do not have a deep practical impact on the country, such as a proclamation celebrating a particular event, like the birthday of Caesar Rodney, a Founding Father from Delaware. Others have a much more significant impact since they can govern the activities of both public officials and private citizens, direct Federal funding to specific programs, and the like. An example of an Executive action directing the activities of public officials and directing how tax dollars were to be spent was President Trump’s declaration of an emergency at the U.S.-Mexican border, which he used to build his signature border wall. The proclamations President Trump used to limit the arrival of non-citizens to the United States during the coronavirus pandemic are examples of Executive actions more directly influencing the activities of private individuals. All in all, the President wields much power through Executive actions.

The President can wield such significant power since he is, at least theoretically, acting pursuant to constitutional or statutory law. The documents typically contain a line, “By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and laws of the United States of America…”, often followed by the name of a specific law that confers the authority to undertake the action. Since they are (theoretically) acting pursuant to constitutional or statutory law, they do not need congressional approval prior to issuing such a document. Congress often passes laws explicitly giving the President discretion in how to administer a law, within some prescribed boundaries. It also passes laws that are so vague as to require the Executive Branch to flesh out the details. The Constitution also vests the President with certain powers, like acting as Commander-in-Chief, which also require discretion in how they are to be exercised. These factors give the President significant leeway in administering the government. Since the President has so much discretion, Administrations may differ wildly in how they carry out the laws. To undo the actions of a previous President, or to undo one’s own actions, a President only needs to issue another Executive action document. In undoing many of President Trump’s actions on the first day in office, President Biden illustrated the degree to which his Administration will differ from his predecessor’s.

To ensure that a particular policy remains in place after they are gone, Presidents ought to work legislation through Congress. Though Presidents cite the Constitution and statutes as the basis of their actions, passing another law limits the discretion they and a future President has over the issue. When a law is adopted, the Executive Branch must administer it, regardless of the President’s policy preferences. The law remains in place until Congress repeals or amends it, even as the Administrations change from one to another. So policies established through an act of Congress have a much more solid foundation than those established merely through Executive action. Creating a policy via law is like planting a tree that can build deep roots; by comparison, an Executive action is more like a weed. When the opposing party comes to office, it can easily pluck the weeds, but taking a tree out by the roots requires more effort.

Creating a policy via law is like planting a tree that can build deep roots; by comparison, an Executive action is more like a weed. When the opposing party comes to office, it can easily pluck the weeds, but taking a tree out by the roots requires more effort.

The Department of Education is an example of the ease of unmaking policy a policy put in place by Executive action compared to one enacted via statute. Over the years, numerous Republicans, including President Ronald Reagan, have argued in favor of dismantling the Department of Education. None have done so because the Department was established by Department of Education Act of 1979, and no subsequent law has eliminated it. On the campaign trail, the incredibly popular Reagan advocated abolishing the Department, but in Washington, he bowed to congressional sentiment: In 1985, he sent a letter to Senator Orrin Hatch, the Chairman of the Senate Labor and Human Resources Committee, backing away from that idea since “that proposal has received very little support in Congress.” By comparison, another Department of Education initiative illustrates how easy it is to overturn an Executive order. To promote civic education, President Trump issued Executive Order 13958, which established the 1776 Commission, housed within the Department of Education. The Commission was charged with studying and reporting on the principles upon which the country was founded, its history, and related topics. Less than a day after Trump left office, it was gone, since President Biden signed an Executive order to dismantle it.

Doing away with the 1776 Commission is only one of the many actions President Biden has undertaken to reverse Trump’s policies. A major action halted the construction of the former President’s signature wall along the U.S.-Mexican border. Another rolls back Trump’s decision to exclude from the U.S. Census those with irregular immigration statuses. President Biden also revoked the permit to construct the Keystone XL pipeline, an underground conduit to transport oil from Canada all the way to the Gulf of Mexico. These are only a sample of the ways Biden has already moved to undo Trump’s agenda, and the new President has pledged additional actions in the first ten days of his Presidency in particular. Had these and other initiatives passed Congress, Trump would not be seeing his actions undone so swiftly.

Presidents use Executive actions since they are far quicker to put in place than laws are to pass. When issuing an Executive order or similar device, the Administration needs to draft a particular policy they would like to pursue and advance a plausible legal justification for it. By contrast, instituting a policy via a law requires it to pass both houses of Congress before the President may sign and implement it. A goes through several rounds of review (like the committee process in both chambers), gatekeepers (committee chairs, party leaders), and negotiations before it can become a law. Even when one party controls the House, Senate, and White House, that can take a long time. If the party opposing the President controls just one of the houses of Congress, passing legislation on a controversial issue becomes all the more difficult. Even when one party controls both Congress and the presidency, enacting laws can be very challenging since the Senate minority traditionally enjoys much leverage over the process and can slow legislation or stop it entirely. Additionally, keeping a legislative majority together on a controversial piece of legislation can be challenging.

In recent years, partisan polarization has increased, and it has been infrequent that either party has had a commanding control of both houses of Congress, especially the Senate. So moving controversial legislation through Congress is difficult. Nonetheless, Presidents are typically eager to see an agenda through, so they use what Executive powers they have at their disposal to put these policies in place, even when Congress can’t or won’t legislate on a policy. When Congress does not do its duty to set national policy, it effectively leaves the President considerable freedom to institute his preferred policies instead of theirs, even though the Executive action may be on shaky grounds. Former President Trump has now seen how quickly one can dispose of policies put in place by Executive actions. He joins his predecessors in that respect. President Bident will eventually join that club, too, since just as he has done to Trump’s Executive actions, a future President will do the same to his too.