The Social Security Fairness Act of 2021 might make it to the House Floor through a rarely successful discharge petition by the end of this Congress. The legislation, H.R. 82, sponsored by Representative Rodney Davis of Illinois, seeks to address an issue where Social Security benefits for public servants at various levels of government and their spouses under certain conditions. The legislation is popular, with 303 cosponsors – almost 70 percent of the House – as of this writing. One key group it is not so popular with is the Ways and Means Committee, which oversees the nation’s tax policy and Social Security. The holdup is that the bill, popular as it might be, would negatively impact Social Security’s solvency, so they would prefer a different solution, one which they say would aid government workers without harming the program. To advance his legislation even in the face of this opposition, Representative Davis, along with Representatives Julia Letlow and Garret Graves, both of Louisiana, has pledged to use a discharge petition, which requires a majority of the House to take a bill out of a committee. It’s a noteworthy use of a discharge petition since it shows how legislation can’t be stopped if a critical mass supports it and how important it is for Members to diligently work their legislation through the House.

How do discharge petitions work?

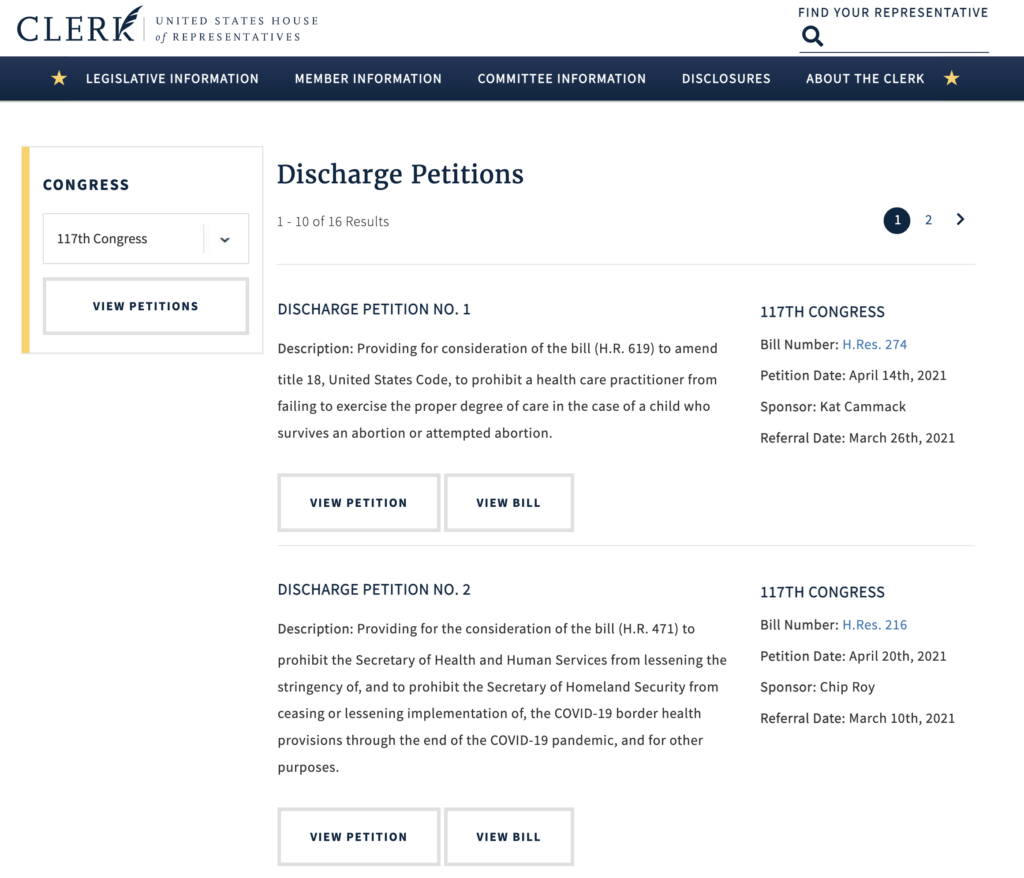

Rule XV, clause 2, of the Standing Rules of the House provides for discharge petitions (or rather the “motion to discharge,” in the terminology of the rules). A Member may present the Clerk with a motion to discharge for a bill that has been referred to a committee for at least 30 legislative days. Alternatively, they may present a motion for a special rule that has been referred to the Rules Committee for at least seven legislative days for a bill that has been referred to a committee for at least 30 legislative days. The Clerk must put the motion in “a convenient place” for the Members to sign it. Once it has garnered enough signatures to equal a majority of the whole House—218—the motion is added to the “Calendar of Motions to Discharge Committees.”

The term “Discharge Calendar” is something of a misnomer. It is more properly thought of as a list of successful discharge petitions than a calendar in the typical sense of the term. And it’s typically an empty list. Each legislative day, the House Clerk publishes this and other “calendars” in the Calendars of the United States House of Representatives and History of Legislation. Congress.gov links to this document in its page containing the House and Senate Floor activities, and it is also available on the homepage of GPO’s GovInfo.gov.

Once the discharge motion is added to the Discharge Calendar, seven legislative days must pass before it becomes eligible for privilege over other motions. If a petition has been on the calendar for seven legislative days, a Member may announce that he or she intends to call it up. Then the Speaker must designate a place for debate on the legislative calendar within two legislative days of the Member’s announcement. The discharge motion is privileged only during that spot that the Speaker has designated.

When the appointed time for the discharge motion has come, the Member calls up the motion, and the House debates the motion for 20 minutes, 10 minutes for those who support it, and then 10 for those who oppose it. If the discharge petition is for a special rule and the House agrees to the motion, the House immediately proceeds to debate the special rule. (A special rule is a resolution that sets the terms for debate and amendment of a bill and includes exceptions to and departures from the established and formal procedures of the House). Assuming the House agrees to the special rule, it then considers the bill which the special rule makes in order. If the discharge petition is for a bill and the motion is agreed to, a Member who signed the petition must make a non-debatable motion to proceed to the bill (without a special rule) in question. Assuming that succeeds, the House considers the bill “under the general rules of the House.”

In the House today, Members often, as a matter of strategy, choose to discharge the Rules Committee of consideration of a special rule that would make their desired bill in order. So, a Member who wishes to use a discharge petition will introduce a special rule which is then referred to the Rules Committee. Discharging the special rule gives them greater control over the debate since they can limit the time spent on the debate, the motions that may be made, amendments, points of order, and the like.

What are the politics of discharge petitions?

The House majority leadership typically says that discharge petitions turn the House Floor over to the minority, which is to say, the minority party. In truth, when a discharge petition succeeds, it is because a bipartisan majority has worked its will over and against what most of the majority party might wish. By definition, to get a majority of the House, some Members of the majority party must sign on to the discharge petition. Nonetheless, with the relatively recent (as far as discharges go) exception of the Export-Import Bank Reauthorization in 2015, the majority party leadership hates to have its control of the Floor undermined, so if there’s a chance that a discharge petition will succeed, they often bring up an alternative version of the bill that will satisfy their Members, making it unnecessary to sign the motion.

What is special about Rep. Davis’s discharge petition for the Social Security Fairness Act?

Since discharge petitions rarely succeed, introducing them isn’t usually noteworthy. Representative Davis’s petition is a different story. His bill has over 300 cosponsors—well over the 218 needed to succeed. So he has more of a shot at succeeding than discharge petitions often do.

One dynamic that is working against Davis is that his cosponsor count is more than 2/3 Democrats and less than 1/3 Republicans. So as of now, 211 are Democrats—almost the entire Democratic Caucus—and 92 are Republicans. Without the tacit consent of the Speaker, many of these Democrats will be reluctant to sign a discharge petition that would be seen as undermining the powerful Chairman of the Ways and Means Committee.

If the numbers were switched, and the vast majority of the Republicans had signed the petition, it would not be as difficult to persuade enough Democrats to defect. Assuming all the Republican cosponsors sign the petition, he’ll still need a considerable number of the rest of the Republicans to sign the petition. Now, the Republicans might sign on simply to embarrass the Democratic leadership, so it might not be too much of a lift, but it’s not a guarantee. On the other hand, as much as a discharge petition would delight the minority, the Republicans might not be too enthusiastic about advancing a bill that has questionable effects on the nation’s fiscal health.

Then he would still need to persuade many Democrats, which could be hard for the reasons stated above. However, if the Democrats lose the November elections, many, particularly those who have been defeated, may be willing to buck their leadership during the lame-duck session. So this discharge petition is still one to watch, especially in mid-November.

What else is there to say about the process for advancing the Social Security Fairness Act?

With the sheer number of sponsors for this bill, it actually qualified for the so-called Consensus Calendar. The Consensus Calendar was created at the beginning of the 116th Congress to provide another avenue for the House to consider legislation that had wide support yet nonetheless did not move through the committee process. According to House rule XV, clause 7, each week that the House is in session, it must consider a piece of legislation on the Consensus Calendar, and the Speaker may select the item for consideration from among those on the Calendar. To be eligible for the Consensus Calendar, a piece of legislation must have 290 cosponsors. Once it does, the bill’s sponsor may present a motion to add it to the Consensus Calendar. Once 25 legislative days have passed, and if the measure maintains 290 cosponsors, the item is added to the Consensus Calendar. Critically, however, if the committee of primary jurisdiction reports the bill during the 25-legislative-day period, the motion is considered as withdrawn and no longer eligible for the Consensus Calendar. Additionally, if the committee also reports the bill once it is on the Consensus Calendar, it is automatically removed from the Consensus Calendar. In both cases, the bill would need to come to the Floor another way (typically through a special rule from the Rules Committee). Thus, the committee of jurisdiction can easily slow down a bill from advancing to Consensus Calendar simply by reporting it and letting it die a slow death in the Rules Committee.

July, Representative Davis made a motion to place the bill on the Consensus Calendar. On September 20, the bill was finally added to it. The very next day, the Ways and Means Committee reported the bill to the House without any recommendation as to whether it should pass. When the Ways and Means Committee held its mark up on the bill, both Chairman Richard Neal of Massachusetts and Ranking Member Kevin Brady of Texas acknowledged the necessity of addressing the issue in a way that supports both public servants and protects the integrity of Social Security, which would be adversely affected by the passage of H.R. 82.

The Consensus Calendar was an idea promoted by a number of Congressional reform advocates as a way to increase rank-and-file Member’s voices on the House floor. But it was written in such a way that the Speaker really has the power through the Rules Committee to block legislation on the Calendar that she opposes. In the next Congress, advocates may want to tighten up the rule to make it work more like a discharge petition. The advantage of the Consensus Calendar over a discharge petition is that it is much easier for a Member in the majority to cosponsor a bill than to directly challenge their own leadership by signing a discharge petition.

Representative Davis’s creative use of the rules to pass his bill demonstrates how diligently working legislation among Members over many years can pay off. Davis entered Congress in 2013 and has introduced this legislation in each Congress to which he has been elected. He started with the Social Security Fairness Act of 2013 in the 113th Congress and got 136 cosponsors. In the 114th Congress, the Social Security Fairness Act of 2015 won over 159 cosponsors. The 2017 version in the 115th Congress got 195. The 2019 version in the 116th Congress achieved 264 cosponsors. And just one day after the current Congress opened, he introduced the Social Security Act of 2021, which has continued to accumulate sponsors, with the most recent being added on September 28. Years of work to build up support for an idea—work he’s continued even after being defeated in a primary election earlier this year—might soon pay off with a legislative win via a discharge petition. We do not take any position on the merits of H.R. 82, and we certainly do not denigrate the motives or position of Ways and Means Committee members and leadership, but Representative Davis’s effort is something to take note of. He may not succeed in getting the signatures for his discharge petition, but his dedication to working an idea through Congress is an example for other Members to follow. And if he does succeed in getting a bill to the Floor via a discharge petition, what a way to leave Congress!