The U.S. Senate filibuster, an attempt to use various parliamentary tactics to slow or stop debate, is perhaps the best known and most controversial legislative practice Senators can engage in. Since filibusters delay the Senate’s business—and, by extension, that of the House and the rest of the government—many people are frustrated with the practice and look for ways to reform it. If Senators decide that the filibuster should be reformed, several options they could choose are presented here. For instance, the Senate could abolish the filibuster entirely, or lower the threshold to invoke cloture. The best venue to discuss changes to the filibuster would be a new Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress, a bicameral, bipartisan panel to consider wide-scale reforms to the legislature.

Introduction

What is a filibuster?

What is cloture?

What is at stake in the controversy over the filibuster?

How has filibustering evolved over the years?

How has the filibuster been reformed in the past?

How can the Senate reform the filibuster today?

How can the Senate still promote the right of Senators to debate and amend while reforming the filibuster?

How can the Senate address problems related to the filibuster today?

Introduction

The original meaning of the word filibuster is “pirate” – and like the pirate Jean Laffite who fought with Andrew Jackson during the Battle of New Orleans, your views towards the filibuster largely depend on which side you are on. The British first saw Lafitte as an ally to be courted, but then a pirate to be hanged, while Andrew Jackson authorized an attack on his base, but then proclaimed him one of the heroes of the battle. Likewise, the majority party in Congress often sees the filibuster as villainous, until they are once again in the minority, while the minority party sees it as the last protection of their political rights, but a scourge on progress once they regain control. Where Senators stand on the filibuster usually and genuinely depends on where they sit.

Justly or not, the filibuster frequently slows down or completely stops Senate business. By extension, it affects the House and business for the rest of the government, too. The dilatory nature of the filibuster makes it highly controversial, and some Senators of both parties and the general public call for reforms. The filibuster has undergone many reforms before (most recently in April 2017), and if the Senators decide filibuster reform would benefit the Chamber, various options they could consider are presented here. These options are a starting point for consideration, and this is not, by any means, a comprehensive list. Various arguments for and against and negative and positive consequences of the different kinds of reform are discussed, but without endorsing any particular option. Additionally, should the Senate decide to change the filibuster, the best way to do so would be by first creating a new Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress to consider possible options in a bipartisan forum.

What is a filibuster?

In the U.S. Senate, a filibuster is an attempt to delay or defeat a piece of legislation or nomination using various parliamentary tactics. The most famous kind of filibuster, known as the talking filibuster, is when a Senator takes to the Floor and continues speaking until he or she can speak no more, as was depicted in the classic film Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. It is made possible by the Senate rule that requires the presiding officer to recognize all Senators wanting to speak unless cloture has been invoked. Though well-known because it is so dramatic, that kind of filibuster is only one among many, since Senators have other ways to delay business. For instance, since the Senate expedites business by dispensing with formal rules by the unanimous consent of its Members, a Senator can slow debate by objecting to such requests. Another way would be to repeatedly point out that there is no quorum, meaning the body would have to go through the process of summoning enough Senators to achieve a quorum.

Using tactics like the ones described above is known as a “live filibuster,” but there is also the less noticeable “silent filibuster.” Senators can do this by “placing a hold” on an item of business. A Senator does this by notifying their party leader that they intend to object to a unanimous consent request, and the party leader typically will prevent the consideration of the measure. Essentially, a hold is a threat to object to a unanimous consent request that prevents a bill from being called up for consideration. It is a silent filibuster when the Majority Leader is not convinced he can get 60 votes to invoke cloture on a bill should a Senator follow through on his or her intention to object, forcing the Senate to consider the legislation through regular order.

What is cloture?

Cloture is the procedure that allows the Senate to vote to end debate on the business before it. A Senator, usually the Majority Leader, starts the cloture process by presenting a petition, signed by 16 Senators, to end debate on the matter under consideration. Two calendar days later, the cloture petition is said to “ripen,” and the Senate votes on it an hour after convening. The threshold for success varies for different kinds of business. For legislation, three-fifths of all sitting Senators—usually 60—must vote in favor of ending debate. For changes to the Senate rules, an affirmative of two-thirds of Senators voting is required. For nominations, a simple majority is required. If the cloture vote is successful, the Senate may spend another 30 additional hours on the question. Additionally, in general, amendments that Senators wish to offer must have been introduced before the cloture petition passed, and they need to be germane to the bill.

What is at stake in the controversy over the filibuster?

The filibuster controversy is an example of the conflict over minority rights and majority rule. The filibuster allows a minority of Senators—whether the minority is defined by political party, economics, geography, or other factors—to check the actions of the majority. It is a powerful way for the minority to protect itself. But since this can block the majority, some call the practice an undemocratic violation of majority rule. In fact, today, Senators in 21 states representing 11 percent of the population can potentially prevent the majority from getting 60 votes (calculations based on data from U.S. Census Bureau). Filibustering does not always prevent a bill from passing, but it can force the majority to moderate the legislation in order to gain the votes needed to force cloture. Moderation is what the Founders would have seen as the main purposes of the Senate: cooling the hot passions of legislation coming from the reelection-sensitive House and driving consensus among the Senators on issues.

How has filibustering evolved over the years?

One of the most notable changes in filibustering has been the increase in their frequency as partisan polarization increases. Filibusters were once rare, but most major legislation faces at least the threat of one. What counts as a filibuster is disputed, but one way to track their frequency is the number of cloture petitions that are filed.

The cloture rule was created in 1917 at the behest of President Woodrow Wilson, who was angry about a Republican filibuster of legislation to arm merchant marine ships prior to the United States entering World War I. In the early years after the Senate adopted the cloture rule, there was no cloture petition in 8 of 21 Congresses. The most recent Congress without a cloture petition was the 85th (1957-1958). However, from around the 87th Congress onwards, cloture petitions increased steadily. They peaked at 252 in the 113th Congress.

In addition to becoming more frequent, filibustering has become physically easier. In the 1970s, the Senate instituted its “dual-track system,” where the Chamber could have multiple items of business pending at one time and switch between them as needed, an option that helps facilitate must-pass legislation (Oleszek, 270). Under the dual-track system, if a bill is being held up by a filibuster, the Senate may consider another item of business, meaning the filibustering Senator or Senators no longer need to continue speaking or making dilatory motions. Also, the use of holds, which means Senators do not need to control the Floor, have increased. Holds were first used in the early 1970s, and according to Senate scholar Steven Smith, “it is hard to exaggerate” the prevalence of holds by the 1980s (100, 171). Filibustering has never been so easy.

As a result of how easy filibusters have become, all kinds of procedural mischief has been conjured up over the last decade to thwart filibusters. Reformers say this partisan back-and-forth invites all sorts of procedural mischief. In response to the minority abuse of the filibuster for partisan reasons, the majority does an end run around them and slights or outright abandons regular order and precedent in the process. For example, the Senate has seen increased use of budget reconciliation, the nuclear option, the filling of the amendment tree and same-day cloture. This abuse and counter-abuse, reformers argue, is destroying the traditions, if not the rules, of the Senate. And if frustration with the filibuster is not in the Senate itself, it is among other sectors of the government, making discussions on reform particularly timely.

How has the filibuster been reformed in the past?

The Senate has reformed the filibuster a number of times. Most notably, in 1917, the Senate adopted the rule governing the cloture process. Ending debate under the original cloture rule required an affirmative vote of “two-thirds of those voting.” In 1949, “of those voting” was changed to “of the Senators duly chosen and sworn.” Additionally, they voted to make filibusters of the motion to proceed eligible for cloture (Arenberg, 25). A decade later, the Senate reverted back to basing the threshold for success on the number of Senators present and voting, not the total number of Senators. In 1975, the Senate created two thresholds for a successful cloture vote. For most business, it required three-fifths all sitting Senators, but for changes to the Senate rules, two-thirds of Senators “present and voting” was required. In November 2013, the Senate Democrats, under Majority Leader Harry Reid, used the highly controversial nuclear option to reduce the threshold for cloture to a simple majority for all Executive Branch nominations and Judicial Branch nominations, except for those to the Supreme Court. (For more on the nuclear option go to this link.) In April 2017, the Senate Republicans, under Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, used the nuclear option to lower the threshold for cloture to a simple majority for nominations to the Supreme Court. (There have been other reforms as well, but they are omitted for brevity’s sake.)

How can the Senate reform the filibuster today?

Many people have offered different proposals to reform the filibuster. Some options include:

-

- Eliminate the filibuster entirely

- Eliminate the filibuster on the motion to proceed

- Lower the threshold to invoke cloture

- Peg the threshold to the size of the majority

- Set threshold to 55

- Ratchet-down of the threshold to invoke cloture

- Require filibustering Senators to hold the Floor

- Refuse to honor holds

- Eliminate the dual-track system

- Reforms to cloture petition timeline and post-cloture debate

Eliminate the filibuster entirely

With the use of the nuclear option in 2013 and 2017, Senators may only filibuster during the various debates related to legislation, like the motion to proceed or final passage of a bill. Eliminating the filibuster entirely for such debates would entail changing the rules to require only a simple majority to invoke cloture for any item of business. Numerous people, both liberal and conservative, have called for the elimination of the filibuster for legislation. Proponents of this reform would note that the concept of majority in the Senate is already skewed by the fact that small states and large states have the same number of votes. Since the Senate is already made up of a majority that over-represents the small states, small states do not need the filibuster to provide extra protection against the House. In 2016, the 25 least populous states—which control half the votes in the Senate—comprised only about 16 percent of the United States population (calculations based on data from U.S. Census Bureau).

Eliminate the filibuster on the motion to proceed

One way the Senate begins debate on a bill or some other piece of business is by voting on motion to proceed to a bill or nomination, which requires a simple majority for adoption. Legislation that is ready for Floor consideration is placed on the Senate Legislative Calendar, and nominations and treaties that are ready for consideration are placed on the Executive Calendar. One way to bring a bill up for consideration is for the Majority Leader to make a motion to proceed. However, the motion to proceed is debatable, so Senators can filibuster, meaning the majority often must muster 60 votes to even begin debating the bill itself. Eliminating the 60-vote requirement for the motion to proceed could be done a number of ways. For instance, Republican Senator James Lankford of Oklahoma wrote in February 2016, “We should change Senate rules for the voting threshold to begin debate on any bill with a simple majority.” Another way to eliminate the filibuster on the motion to proceed is by limiting the amount of time available for debate on the motion. At the beginning of the 113th Congress, in January 2013, veteran filibuster reformers Senators Tom Udall, Jeff Merkley, and Tom Harkin introduced a resolution to change the Senate rules, which included a provision to limit debate on the motion to proceed to two hours, equally shared by the majority and minority parties.

Lower the threshold to invoke cloture

If the Senate did not want to eliminate the filibuster entirely or just for the motion to proceed, it could still make ending debate easier by lowering the threshold for cloture to something less than what it is now, but still more than a simple majority. One option would be to make the threshold for a successful cloture vote on a legislative filibuster equal to the total number of sitting majority-party Senators, including independents caucusing with them. This would mean the threshold would rise and fall according to the size of the majority. It would make cloture easier to achieve since the majority would not need to rely on any minority party votes to succeed. At the same time, it should still have a moderating effect on legislation, since the majority would still need to rely on the votes of those Senators closest to the ideological center (who are also often those who are the most vulnerable to being unseated in the next election). If any majority-party Senators voted against cloture, the majority would need to rely on minority votes to end debate, meaning the threshold would still promote moderation. This threshold for cloture would also take away both parties’ favorite Senate talking point: The minority party is obstructing. With this threshold, if the majority is unable to stay together simply to end debate, they only have themselves to blame for failing to develop a consensus around the business at hand.

Another potential threshold for a successful cloture is 55 votes in the affirmative. This number is the statistical mode for the size of the majority since the 86th Congress, the first time the Senate had 100 seats (calculations based on data from Senate Historical Office). The benefit of this threshold for a majority is that it is not uncommon for the majority party to have this many seats, and if the majority is larger than that by even a handful of seats, it becomes all the easier to obtain cloture. If the majority is smaller than 55 Senators, the majority is still forced to obtain the buy-in of the minority party to conduct controversial business.

A third way to reform the filibuster is to lower the threshold each time a cloture vote fails. In 2013, former Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa introduced a resolution to achieve this. The resolution stipulated that the majority for the first cloture vote on a measure was three-fifths of all sitting Senators (60 votes). However, each time the cloture vote failed, the threshold for a successful vote would be reduced by three. If the vote reduction would put the threshold below a simple majority, the threshold would automatically become a simple majority of all Senators (51 votes).

| Cloture Vote | First | Second | Third | Fourth | Fifth | Sixth | Seventh, etc. |

|

| Threshold to Invoke Cloture | Legislative Filibuster | 60 | 57 | 54 | 51 | 51* | 51* | 51* |

| Rules Filibuster | 67 | 64 | 61 | 58 | 55 | 52 | 51 | |

| *Members typically vote along party lines on procedural votes, so it is highly unlikely that the majority party would fail to achieve 51 votes for cloture on the first attempt when the threshold is a simple majority. | ||||||||

When debating this proposal in 2013, Senator Harkin argued that the minority should be allowed to delay the process, not stop it. The proposal “would protect the filibuster as a means of slowing things down, but eventually the majority would be able to act, and that is as I think the Founders and the drafters of our Constitution really meant it to be.” This rule would still allow the minority to slow down debate. In 2010 testimony before the Senate Rules Committee, Senator Harkin spoke of this process taking eight days, which he said would prompt the majority to compromise with the minority rather than spend all that time on cloture. Although rule changes are often proposed, but rarely voted on, the full Senate considered this idea, defeating it by voice vote in January 2013.

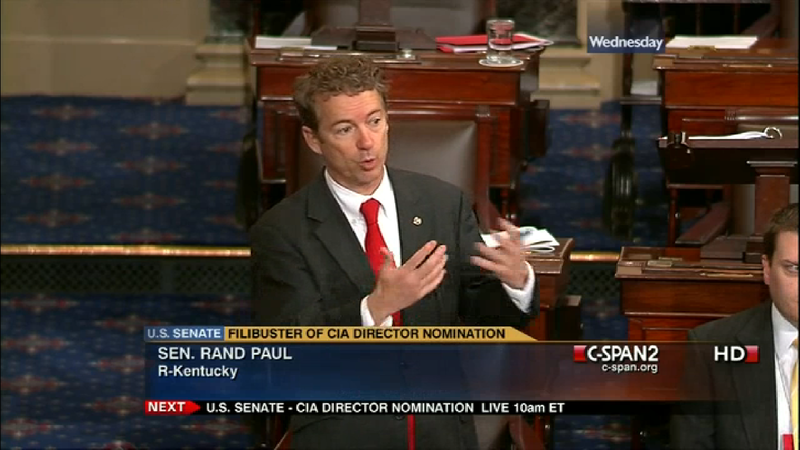

Require filibustering Senators to hold the Floor

Speaking for as long as possible on the Senate Floor is only one way to filibuster, but it symbolizes the practice. Aside from the sheer drama of the so-called talking filibuster, there is good reason for this: If the Senate is the place for extended debate, minority Senators who want to prevail upon the majority should attempt to persuade their colleagues through their arguments. Granted, talking filibusters are not entirely specimens of excellent rhetoric: Senator Huey Long, for instance, shared his recipe for fried oysters in a 1935 filibuster. The longest filibuster in Senate history was conducted for 24 hours and 18 minutes by Strom Thurmond, at the time a Democrat from South Carolina, trying unsuccessfully to derail President Eisenhower’s Civil Rights Act of 1957. Requiring a talking filibuster would at least place a greater burden on Senators who wish to hold up legislation.

One reason Senators do not filibuster in person is the hold. As mentioned previously, the hold is a notification that a Senator will object to a unanimous consent request, which his or her party leader honors by preventing consideration of an item of business. Party leaders enforce holds partly as a courtesy to their colleagues and partly so that a live filibuster does not bog down the Senate. Holds are simply a customary practice and not an actual Senate rule, so party leaders could simply refuse to enforce them. This is reform is conceptually simple and requires no rule changes, but it would likely generate some tension among a caucus if its leader announced that he or she was eliminating or reducing holds. If a leader refused to honor holds, the legislative process could still be slowed down if like-minded Senators hung around the Senate floor prepared to object to any unanimous consent requests. However, if Senators were forced to engaged in live filibusters, for their own sake, they would need to be judicious in their decision to object. Another issue with eliminating holds is that it would eliminate legitimate purposes of the hold, such as providing Senators more time to examine an issue, request information, or force a change in a bill. However, Senators may still achieve these purposes through lengthy Floor debate and a robust amendment process.

Spectacular live filibusters are also uncommon because of the Senate’s aforementioned “dual-track” system. Although the dual-track system lets the Senate attend to other important business, like appropriations that prevent government shutdowns, it also means filibustering Senators do not need to speak continuously. If the Senate reverted to a single track, Senators who wanted to filibuster would need to make a concerted effort to do so. Conducting a solo live filibuster is physically exhausting, which is one of the reasons they used to be rare. But, eliminating the multi-track system to force live filibusters would come at a high price for the schedule: Important legislation could be delayed. If the delayed legislation were a new appropriation that did not pass before the old one expired, the relevant government operations would be suspended. If the Senate eliminated the dual-track system, ensuring that critical bills pass in a timely manner would become even more difficult.

Reforms to Cloture Petition Timeline and Post-Cloture Debate

In addition to abolishing the filibuster or reforming the threshold for cloture, the Senate might find it desirable to address a couple additional points regarding the closing of debate—points that commentators generally overlook when discussing rule XXII. In addition to establishing the supermajorities to invoke cloture, rule XXII currently provides a timeline governing when the Senate should vote on cloture (2 days following the presentation of a cloture petition) and it also provides for up to 30 “hours of consideration” after cloture is invoked. The original wording of the cloture rule permitted each Senator an hour of debate time after cloture, but this has been reduced over the years. Senator James Lankford of Oklahoma has proposed reducing the period from 30 to 8 hours. The Senate temporarily instituted this rule in 2013, but it was only in effect for the 113th Congress. While adopting Senator Lankford’s or a similar proposal would leave the filibuster in place, the tighter time limits might make it more tolerable to the majority party.

If the Senate lowered the threshold for successfully invoking cloture, it would also be an opportune time to consider whether to keep these provisions of rule XXII as they are or modify them. Additionally, these aspects of rule XXII could be reformed even if the remaining supermajority requirements to end debate are retained.

How can the Senate still promote the right of Senators to debate and amend while reforming the filibuster?

There is no doubt that reforming the filibuster in the ways described above cuts down on Senators’ right to extended debate. The Senate, however, could still attempt to preserve the right to extended debate even while reforming the filibuster. Rule XXII currently allows the Senate to extend post-cloture debate if three-fifths of all Senators vote in favor of it. Not surprisingly, it is extraordinarily difficult for the minority to coax enough majority-party Senators to vote to extend debate. However, the Senate could reform this part of rule XXII. There are several combinations of reforms that would empower the minority. First, and most importantly, it could lower the threshold to extend debate. The threshold could mirror whatever the Senate sets as the threshold for cloture. To truly empower the minority, it could even lower the threshold to a simple majority, which gives the minority a greater chance at extending post-cloture debate. Additionally, the part of rule XXII that allows the Senate to extend post-cloture debate currently allows only one such motion per calendar day. The Senate could change rule XXII to allow multiple motions per calendar day.

How can the Senate address problems related to the filibuster today?

Changes to the Senate rules require a supermajority of two-thirds of Senators present and voting to end debate. On a good day, this is a major obstacle to those who want to reform the rules significantly. Today, it would probably be an insurmountable barrier to changing the legislative filibuster, since too few majority Senators support reform. For instance, on April 7, 2017, the day after the Senate invoked the nuclear option for the filibuster of Supreme Court nominees, 61 Senators, including 28 majority Republicans, signed a letter urging the Majority and Minority Leaders “to preserve existing rules, practices, and traditions as they pertain to the right of Members to engage in extended debate on legislation before the United States Senate.” The following month, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said, “There is an overwhelming majority on a bipartisan basis not interested in changing the way the Senate operates on the legislative calendar.”

Aside from insufficient political will to change the filibuster, would-be reformers face additional challenges. The filibuster affects virtually all aspects of Senate business and, by extension, that of the House and the rest of the entire government, so it contributes to wide-scale congressional logjams, which is why Members of the House frequently lambast the Senate for its ability to make legislative progress resemble the flow of molasses in the winter. However, changing only rule XXII will not, by itself, remedy congressional dysfunction. Eliminating or vastly weakening the filibuster will not likely promote civility or bipartisanship. In fact, reforming only the filibuster could simply provide new reasons and occasions for partisanship, potentially exacerbating the already troubled relations between Republicans and Democrats. Although the filibuster would be limited, the minority could attempt to use other procedural tools available to obstruct the process (like objecting to unanimous consent requests), which would invite further retaliation from the majority, resulting in more acrimony. If there is any doubt that the Senate would be just as partisan as it is today, or more so, look at the highly majoritarian House, where the party in control can conduct its business swiftly, but where relations between the Republicans and Democrats are nonetheless poor. These considerations suggest that, if the Senate decides filibuster reform is necessary, it should be done within the context of a wider congressional reform, including attempts to strengthen bipartisanship and civility.

Given the difficulties of reforming the filibuster, Congress could create a Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress as a forum to discuss ways to improve its debate. Since the 1940s, Congress has created three bipartisan Joint Committees on the Organization of Congress to examine how the legislature could be modernized and made more effective. Past joint committees have recommended changes in the committee system, staffing, the budget process, the calendar, and virtually all aspects of the legislative process. Congress has adopted various recommendations from these committees, making them important catalysts for change on Capitol Hill.

One of the major benefits to creating a new Joint Committee on the Organization of Congress is its scope. The Senate could simultaneously consider reforms to other aspects of the legislative process, like appropriations and the calendar. The filibuster affects matters like appropriations and the congressional calendar, but such issues also have other problems that require resolution. The Joint Committee would have the jurisdiction to address all issues afflicting Congress at one time (though in the past, the House and Senate members of these committees have only considered rules affecting their own Chamber and not the other one).

Additionally, a Joint Committee is an opportune way to discuss ideas to reform the filibuster because it is bipartisan. In recent years, the Senate has tended to have small majorities, so, until the 2013 use of the nuclear option, the majority party has been wary of changing the filibuster in part because it has known that it could very well be in the minority in the next Congress. This was essentially a defensive pose, but it resulted in a consensus—however uneasy—that the filibuster should remain in place. The 2013 and 2017 uses of the nuclear option jolted that consensus, but both Republican and Democratic Senators still want the filibuster to remain in place in some form. To ensure that that bipartisan consensus about Senate rules continue, Senators should examine ideas for reform during a Joint Committee, as it would have equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats. Since it would be equally divided, the Joint Committee could only recommend changes if at least one minority-party Member voted for a proposal. Given the variety of opinions on the filibuster within both the Republican and Democratic parties, it is even likely that multiple minority-party Senators would need to vote in favor of the recommendations. Keep in mind, that if the Senate does not use the nuclear option to reform the filibuster, two-thirds of the Senate is required to end debate on a rules change, so bipartisanship is essential.

Even if the Senate did not reform rule XXII after a fair, thorough and open debate, the Chamber would benefit, since it would reaffirm that the filibuster as it stands is essential to the institution. No doubt many would be disappointed with the result, but seeing that the Senate followed a fair process lends credibility to the institution, and with congressional approval ratings at historically low levels, Congress should try to restore trust and confidence among the American people. If the Senate undertakes it robust debate on the filibuster, it will live up to its moniker: The World’s Greatest Deliberative Body.

A printable PDF of this report may be downloaded here.

Printed Sources Cited

Arenberg, Richard A. and Robert B. Dove. Defending the Filibuster: The Soul of the Senate. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Oleszek, Walter J. Congressional Procedures and the Policy Process, 9th edition. Los Angeles: Sage-CQ Press, 2014.

Smith, Steven S. The Senate Syndrome: The Evolution of Procedural Warfare in the Modern U.S. Senate. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014.