Earlier this month, Senator Ben Sasse offered some ideas on how to “Make the Senate Great Again” in The Wall Street Journal. Sasse communicates effectively and thinks creatively, so it is good to see him offer concrete solutions to improve the Senate. Though he focuses on the Senate, many of his critiques apply to Congress as a whole—and it’s not pretty.

Sasse’s most important line is buried at the end of the column: “Over years, Congress made the choice to shirk its duty and cede power to the Executive Branch.” On this, Sasse is right. For too long, the Presidents (of both parties) have taken too much power for themselves, at the expense of Congress. The Legislative Branch is complicit when it fails to reauthorize programs or enact proper spending bills. And as Sasse notes, “The budget process is completely broken.” The way Congress budgets, it misses out on critical opportunities to direct how the government’s money is spent and to hold the Executive Branch accountable. Fixing the budget process should be Congress’ priority and reclaiming power from the Executive should be its priorities. The Senator is on very solid ground on this point. In our view, the growth in the power of the Presidency is inversely related to the loss of legislative power caused by congressional dysfunction.

Reclaiming power from the Executive Branch will require a collective, bipartisan, bicameral effort. In today’s highly polarized climate, is such bipartisanship possible? Sasse’s 2018 book Them: Why We Hate Each Other—and How to Heal could provide the answer. In Them, Sasse writes eloquently and perceptively about cracks in American culture. He points out, among other things, the necessity of building stronger communities, respectfully engaging with others of differing views and of toning down the elements that divide us. Echoes of Them reverberate in Sasse’s column from last week. Some of his ideas—cutting cameras from hearings, forcing Senators to live together, packing the Floor with Senators—all speak to the need to build up relationships between people (whether or not each individual idea is actually advisable). Certainly, the Senate (and the House even more so) need stronger relationships among Members. Stronger relationships are indispensable since they provide the network to actually move legislation through Congress. A good idea alone is not enough—it takes plenty of good people carrying a good idea forward. Good people enacting good legislation is the only way Congress can reclaim its power from the Executive Branch.

Though Sasse’s overarching goals are laudable, his ways to get there would be effective to varying degrees. One proposal is particularly wrong-headed: Abolish standing committees and replace them with “temporary two-year committees, each devoted to making real progress on one or two big problems.” For one, committees are how Congress manages to deal with hundreds of complex issues each year. Besides, abolishing committees would be nearly impossible politically speaking. Simply realigning committee jurisdictions provoke some of the largest battles among Members—abolishing them completely would be apocalyptic. When you realign jurisdictions, you say to a Chairman, “You’re losing some power, though you might a little in another area.” When you abolish committees, you say to a chairman, “You’re losing all of your power.” Such an effort might even be as disruptive as the nuclear option, and, to make matters worse, it would divide the majority party (whichever party that is). It’s almost a guarantee that the effort would go nowhere.

There’s a deeper reason that Sasse’s committee abolition proposal should go unheeded. Standing committees counterbalance an excessively strong party leadership. In recent decades, party leaders in both the House and Senate have come to dominate the process. Abolishing standing committees would accelerate that process. After all, who would choose the subject matter for the temporary committees? Party leadership? An alternative to that would be the majority caucus as a whole, but that would simply make the ad hoc committees of the majority. Doing so is problematic would disadvantage the minority party, which would run counter to the Senate’s consensus-oriented culture. Keep the standing committees right where they are.

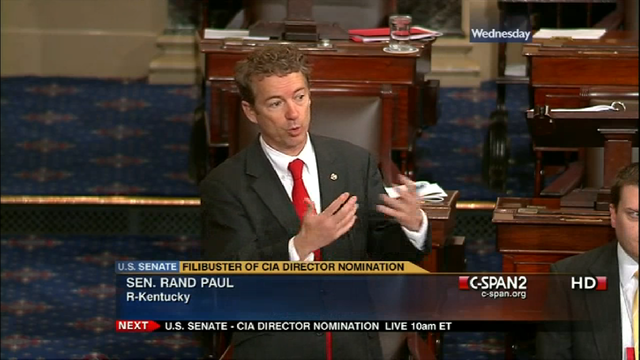

One issue Senator Sasse leaves largely untouched is the filibuster and the effect it has on the ability of the Senate to get anything done. This is a lost opportunity. While some, including former President Obama, would like to abolish the filibuster altogether, a better reform might be restoring the filibuster to its original form, where Members would have to hold the Floor and speak for hours on end. Senators would still filibuster some things, but it’s highly unlikely a Senator is going to speak for 15 hours and annoy his or her colleagues to death over a district court judge, whom the filibusterer and their colleagues will vote in favor of anyways.

Reforming Congress is vitally important and Senator Sasse has done a service by proposing several ideas worth discussing. Better still would be a joint select committee of the House and Senate to really get into exploring and recommending reform ideas that help the legislative branch return to its proper place in the constitutional structure of our government.