Build Back Better was one of President Joe Biden’s slogans for the 2020 presidential election, and the House passed a massive spending bill bearing its name today. The bill (H.R. 5376), which according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) costs about $1.7 trillion over a decade, would fund a diverse assemblage of programs, including those related to cybersecurity, wildfire prevention, childcare, healthcare, climate change and so many others. Much to the consternation of President Biden, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, two Senators from West Virginia, the Mountain State, are posing formidable obstacles its passage. One of these Senators, Robert Byrd, has been dead for over 11 years, yet a Senate rule bearing his name has significantly shaped how each Chamber of Congress is drafting the legislation. Further, due to the 50-50 partisan split in the Senate, each Democratic Senator can effectively veto the legislation, and Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia, well, he has problems with the bill as it currently stands.

Congress is enacting this massive bill through the reconciliation process, which is where Senator Byrd’s influence comes in. Reconciliation is an optional feature of the Federal budget process that helps the Legislative Branch achieve its budgetary goals for the year. Per the Congressional Budget Act, which is the foundation of the budget process, the two Chambers must establish a single budget each fiscal year. The budget may include reconciliation instructions, which direct one or more committees to produce legislation that has a budgetary effect, whether it is changing spending or revenues or adjusting the debt limit. Reconciliation bills are legislation that achieve the goals of these instructions.

By law, in the Senate, debate on reconciliation bills, amendments, and any relevant motions is limited to 20 hours. This time cap means Senators may not filibuster the reconciliation. Since that is the case, the majority party does not need to worry about rounding up 60 votes to end debate via a cloture motion. Though Senators who vote for cloture do not need to vote in favor of the legislation itself, the supermajority threshold to end debate tends to moderate legislation. Since reconciliation makes cloture unnecessary and all that is needed is a simple majority to enact the legislation itself, the majority can make the bill more liberal or more conservative than it would be under the Senate’s usual procedures.

Bypassing the filibuster makes reconciliation powerful. So powerful, in fact, that Senators began to use reconciliation to enact policies unrelated to the budget. The Senate tried to combat abuses with the Byrd Rule, which we discussed extensively in 2017, when the Republicans used reconciliation to enact tax reform:

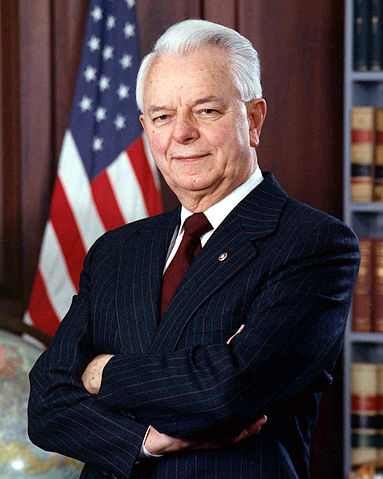

In 1985, to prevent an abuse of the process, the Senate first adopted what is known as the Byrd Rule, which allows Senators to raise points of order against provisions that are considered “extraneous,” meaning they do not contribute to the goals of reconciliation. When debating the rule, its namesake, Senator Robert Byrd of West Virginia, said, “It was never foreseen that the Budget Reform Act would be used” the way it was. According to him, Senators had so abused reconciliation that “any measure, no matter how controversial” could “be brought to the Senate under an ironclad built-in time agreement that limits debate.” This short-circuited “the deliberative process in this U.S. Senate—which is the outstanding, unique element with respect to the U.S. Senate.” In other words, the Byrd Rule attempts to ensure that the Senate still thoroughly vets important legislation. To enforce the Byrd Rule, Senators may raise a point of order against a provision if they think it fails one of six tests. For instance, the first test is whether the provision “produces a change in outlays or revenues.” The process of vetting a bill to see if it meets the rule’s requirements is called a Byrd Bath – really, we are not making these puns up. If a Senator raises a point of order against a provision of the reconciliation and the Presiding Officer sustains the point of order, the provision is removed from the bill and may not be included again via an amendment. Staff refer to the offending amendment as a “Byrd Dropping.” (However, the point of order can be waived if 60 Senators vote to do so.)

The Byrd Rule can deal a death blow to important provisions in a piece of legislation if they do not advance the goals of the annual budget resolution—though Senator Byrd has been dead for over a decade, his rule still influences legislation.

Not surprisingly, the architects of the Build Back Better Act fear the Byrd Rule as Senators will circle the Senate Floor like birds of prey to pick it apart. One area to watch is immigration policy. The bill would temporarily shield from deportation some 7 million in the country illegally. Publicly, the White House is confident that the provision will pass muster. “The framework will also improve and reform our broken immigration system consistent with the Senate’s reconciliation rules,” it says on its website. Yet previous iterations of immigration reform policy were scrapped earlier in the planning process since the Senate Parliamentarian, the Chamber’s non-partisan expert on the rules, advised that the proposals violated the Byrd Rule. (The Parliamentarian’s advice has, from time to time, so annoyed some that you may hear suggestions that the Presiding Officer should ignore her advice. For more on this idea, see “Biden and Bernie vs. Byrd on the Budget”.)

The House does not have the Byrd Rule as such, yet its effects are felt there too, since any reconciliation legislation they send to the Senate must pass its tests. In September, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi sent her Democratic colleagues a letter about the Build Back Better Act, informing them, “We must be prepared for adjustments according to the Byrd rule”. In particular, House leaders have been concerned about what the Byrd Rule means for immigration policy. In early November, House Judiciary Chairman Jerrold Nadler of New York acknowledged the difficulty of assembling a Byrd-friendly immigration proposal. “We’re looking for something that will pass muster with the parliamentarian,” he said. Majority Leader Steny Hoyer also acknowledged the effect the Byrd Rule had on immigration policy by noting, “And if it is held to not be consistent with the reconciliation process then we’ll have to do it some other way because it needs to be done, we need to fix this immigration system.” No matter how much House Members might dislike—nay, despise—the Byrd Rule, they must accommodate it. Whether the current version will survive remains to be seen.

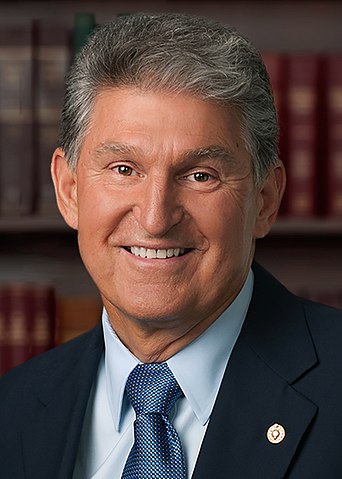

Though the Byrd Rule is undoubtedly important in determining what the final reconciliation bill will look like, far more important today is the size of the majority in each Chamber. This is where Senator Manchin—rather, every single Senate Democrat—is pivotal. As of November 18, the Democrats control 221 seats in the House and 50 in the Senate. Assuming everyone votes, only four Democrats in the House and none in the Senate may vote nay. Even a small handful of Democrats can block the bill in the House, and just one defection can do the same in the Senate. To pass the Build Back Better Act, party leaders need to satisfy everyone in the Democratic Caucus in each Chamber. Working towards unanimity has been a challenge. Earlier this year, Senator Manchin and fellow moderate Senator Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona objected to their party’s initial plans for a bill costing $3.5 trillion. Now it costs $1.85 trillion (according to the CBO). Free community college and an expansion of Medicare have already been cut from the original plans. Senator Manchin, however, has publicly expressed concern over the bill in recent days. Though the Build Back Better Act has passed the House, due to Senator Manchin’s concerns, whatever the Senate passes will look very different—if it passes anything.

If the Senate changes the Build Back Better Act to win Senator Manchin’s vote, it’s right back to the House. The Senate will likely pass legislation acceptable to moderate House Democrats, but the progressive wing of the party will likely be displeased with it. They will either need to begrudgingly accept what the Senate sends them, or party leaders will need to work out another round of compromises that will secure enough votes in each Chamber. Brokering a compromise acceptable to the House moderates and progressives, Senator Manchin and the Byrd Rule will be a difficult achievement.

Though the Democratic leadership will do everything they can to pass the Build Back Better Act, whether and how they do it is not clear. With such small majorities in both Chambers, they do not have room for error. Senator Joe Manchin—yea, almost every single Democrat in Congress—will be decisive and needed for victory. As if that wasn’t hard enough, the Byrd Rule is an additional constraint on leaders. Thanks to two Mountain State Senators, one living, one dead, President Biden, Speaker Nancy Pelosi, and Senate Majority Leader have one heck of a legislative mountain to climb.