Campaigns and elections for Congress are grueling. Getting elected, though, is the easy part. Governing—to say nothing of governing well—is much harder.

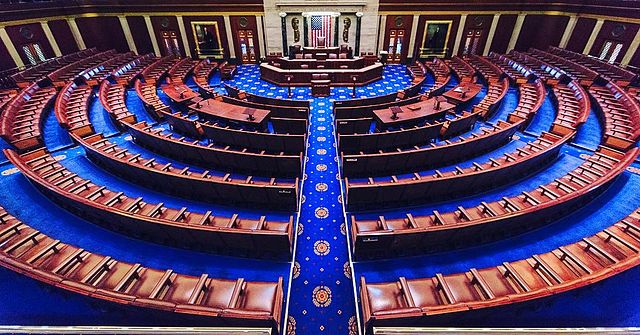

The House of Representatives has the opportunity to wipe the slate clean and begin again every two years. Unlike the Senate that considers itself a perpetual body, the House is designed to be more responsive to public demands. One demand is for Congress to get its act together and reform its processes and procedures. Processes and procedures are the tools for governing. Some tools need to be sharpened, while others should be discarded.

The House of Representatives majority sharpens and discards its tools on the first day of each new Congress when it offers its rules package. The rules package is a resolution that re-adopts the rules of the previous Congress with some modifications. Agreeing to a rules package gives the House the opportunity to take stock of how it operates and decide how it will proceed for the next two years. This is especially true when one party reclaims control of the House and ushers in a new approach to governing. Since the now-minority Republicans are favored to win the 2022 elections, the House could—should—see a new approach to governing in January.

Principles for Reform

Republicans have complained bitterly about how the Democrats have governed the Chamber. If they take the majority, they may either continue in the same vein or provide an alternative vision for the People’s House. Leaders from both parties have governed the House with a heavy hand for too long, so a new way forward would reinvigorate the Chamber. Republican leaders can strengthen the House by prioritizing reforms that increase civility and improve cross-party relations, strengthen congressional committees, encourage debate on the Floor, and work to restore Congress’ Article One powers that have been weakened over the last several decades. Promoting these goods will strengthen the House and result in greater legislative output for the country.

Civility is the bedrock of a functioning legislature. As in any other sector, Members like working with people who don’t jerk them around. The parties too often forget that basic fact of human psychology. In fact, though cross-partisan incivility occupies most of the public’s attention, it’s important to promote civility within a party too, especially for the majority, which is expected to govern, i.e., work with each other. Civility allows parties to govern effectively since it increases the likelihood that Members will be able to offer ideas and their colleagues engage with them thoughtfully. The best ideas can survive the legislative process and others can be set aside respectfully. Congress’ best work is not possible without civility – in fact, one of the purposes of House rules is to foster a respectful and civil process for passing legislation. Members don’t have to love each other, or even like each other very much, but they owe their constituents, the Constitution and their colleagues respectful engagement and consideration.

Related to civility, strengthening cross-party relations is critical, too, since large coalitions provide the votes necessary to pass long-lasting, transformative legislation. The country’s sheer size and diverse population means Members represent conflicting interests. Even the Members of a given political party don’t all have the same interests and goals despite the fact that the parties are far more ideologically homogeneous than they were decades ago. Though we live in a democracy where majority rules, consensus allows decision makers to settle difficult policy questions more definitively. Too often today, a party will come to power, enact a policy, get booted from office, and the next majority will try to undo it. This happens since the majority enacts a policy on a party-line vote, rather than a bipartisan basis. With party-line votes for major pieces of legislation, the citizens from the other party and the middle become enraged and vote the majority out. Bipartisan coalitions counteract this see-saw. The country has numerous vexing policy problems, like border security and immigration reform, unsustainable entitlement programs, threats from foreign nations, and so many others. Bipartisan unity around well-crafted policies will solve these issues most effectively, so the House must promote healthy bipartisan relationships. We are not a one-party system, nor would we want to be. The Framers of our Constitution designed our government to do its best work by arriving at a consensus.

Campaigns, unfortunately, complicate the process of finding consensus. The campaign arms of each party see every election as a play for all the marbles. But, a majority party should take a longer view. By allowing for bipartisan cooperation, a majority increases its chances of enacting meaningful legislation. That, in turn, makes the voters more likely to keep them in the majority the next election. Good governing can be good politics, too, if the country benefits.

The prospect of large coalitions advancing transformational legislation raises an important question: Where will such legislation come from? Ideally, the House’s committees will report major legislation. Traditionally, committees have been the locus of legislative activity. But over the last few decades, congressional leaders, particularly the Speaker, have dominated the process of drafting legislation. Fewer and fewer legislators, especially the rank-and-file and minority-party members, have say over the outcome of bills that come to the Floor. The decline of Member participation is a great loss, since each Representative has unique insights and experience to share. The most important insights each Member has to offer are their constituents’ views. The constituents of the Member from Ames, Iowa, deserve to be represented just as much as those of San Francisco or Bakersfield, California. Strong, active committees are arenas where Members may represent their constituents and perfect legislation.

Perfecting legislation and representing constituents does not end in the House’s committee rooms. These processes continue on the House Floor. However, debate on the House Floor has become anemic. In times past, debates were dynamic and sometimes even unpredictable. In fact, only a few decades ago, it was considered poor form for a Member to rely on papers for a prepared speech in debate. Today, spontaneity is not nearly so well prized. Prepared speeches aside, the House’s debates are tightly scripted, primarily through special rules that limit opportunities for amendment and waive points of order against legislation. There are some legitimate reasons for controlling debate, but the Floor has lost too much of its dynamism. Clamping down on Floor procedure means Members, for the most part, do not have the opportunity to represent their constituents as fully as possible. Reforming the way the House debates will empower Members, and, by extension, the people too.

The new majority might seek revenge for past wrongs, or impose the same restrictions on the new minority. Republicans should resist that temptation. Certainly they are not happy with the current state of affairs in the House, but neither are many Democrats. Legislators should legislate. But right now, the House is less spontaneous and open than most town, city, and state legislatures.

The House can do better. Americans deserve better.

With these general principles in mind, there are more than a few concrete proposals that the House can implement to improve how it legislates.

Before all else, the House must abolish proxy voting. The very definition of the word “congress” is the idea of bringing people together. Members can reach compromise when talking to their colleagues. Just the process of getting to know each other personally reduces uncivil behavior, since a Member is far less likely to hurl gratuitous insults at a friend. The experiment with proxy voting that began during the pandemic has been fraught with abuse and, if anything, further contributed to partisan polarization. If school children can return to class, Members of Congress can return to the Capitol.

Civility and Bipartisanship

Promoting civility and bipartisanship may prove to be among the most elusive reforms, though the most necessary too. Civility in Congress is primarily a product of each Members’ good will. Notable acts of incivility poison the atmosphere and the cumulative effect of small offenses injure the relations among Members. Only a little incivility can set the process back significantly. The Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress, however, is a model for the rest of the House. Its chairman, Representative Derek Kilmer (D-Washington), has cultivated a civil atmosphere since the Select Committee was created in January 2019. Chairman Kilmer has achieved this in part through experimenting with committee practices, like alternating seating between the parties during hearings, rather than arraying Democrats on one side and Republicans on another. Plus, the Select Committee has already made several recommendations around civility and bipartisanship. One of the most important of these is bipartisan retreats for Congress. Offering Members the opportunity to interact in an informal setting will do wonders for promoting camaraderie and collegiality. The Congressional Institute sponsored bipartisan retreat in the past, and Members enjoyed them greatly, many of them saying so on the House Floor. For instance, after the 1997 bipartisan retreat in Hershey, Pennsylvania, Rep. Thomas Sawyer (D-Ohio) said, “While we are accustomed to having House Democrats gathered for retreats and Republicans holding separate retreats, I can say that the Hershey retreat was truly bipartisan…By the time we were ready to return home, it was obvious that all who attended the retreat felt a sense of kinship” (Congressional Record; March 19, 1997; H1158-9). The Legislative Branch Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2022 provided $500,000 for a bipartisan retreat for the House. With an election just months away, we shouldn’t expect too much movement on bipartisan retreats this calendar year, but the next Congress should make them a priority beginning in January.

Strengthening Committees

Strengthening committees consists of two parts. The first is to require them to do their jobs—i.e., report legislation. One way the House can promote proactive committee work by enforcing the current rules prohibiting unauthorized appropriations, leaving government programs liable to losing money if the committees of jurisdiction do not authorize them. Further, it could adopt a mechanism like that created in the proposed Unauthorized Spending Accountability (USA) Act (H.R. 2056), which sequesters money from programs that are unauthorized and then eliminates funding entirely if they remain unauthorized. In other words, implementing both these ideas would make the authorizers feel the pain of their inaction. Congress’ oversight power comes from its ability to punish and reward Executive Branch departments and agencies through the authorization process. When committees do not pass authorization bills they lose their leverage over the parts of government they are in charge of overseeing.

The second way to strengthen committees is to prevent the House from bypassing them. The House should refrain from considering legislation that has not been marked up or reported from a committee. To the credit of the majority Democrats, the House adopted a separate order in the 116th Congress prohibiting the practice of considering legislation that had not been reported or marked up (with some exceptions). Then in the 117th Congress, the Democrats added this separate order to the standing rules of the House (rule XXI, clause 12). Both actions were praiseworthy, as both parties regularly say legislation should go through committees. Nonetheless, in the 116th Congress, the House waived the separate order 10 times, mostly for legislation with little or no Republican support. Between the start of this Congress and the end of February 2022, they waived rule XXI, clause 12, at least seven times, according to a Rules Committee staffer. Two of these bills had no minority support and one had only a single Republican supporter. (Two, however, were very strongly bipartisan with almost all Republicans supporting the bills.) So while the rule requiring mark ups is good, it could be shored up by requiring a supermajority vote to waive it.

Floor Procedure

Debates on the Floor of the House should matter again. They should not simply ratify whatever the majority party leadership pre-ordains. The House can do this several ways.

1. Increase the frequency of open rules. The House leadership limits debate by preventing amendments entirely or allowing votes only on those that the Rules Committee has pre-screened. During the 116th Congress, there were no open or modified open rules, so opportunities for amendment were severely curtailed. Open and modified open rules should be the norm. Closed or structured rules should require a supermajority to adopt. To maintain some order over the amendment process, however, the House should still be allowed to set a time limit on consideration of amendments or give priority consideration to amendments pre-printed in the Congressional Record by a simple majority vote.

2. Stop waiving points of order. The rules are practically meaningless if the House simply ignores them. Waivers expedite business and allow the majority to control the outcome. But in doing so, the House loses the potential benefits the waivers provide. For instance, by waiving the various budget enforcement rules, it becomes that much easier for the House to drift further and further into fiscal irresponsibility. Or when the House waives rule XXI prohibiting unauthorized appropriations, it misses opportunities to hold the Executive Branch accountable for how it spends tax dollars. Some rules, if not all, should be waived only by supermajority vote.

3. Restore the motion to recommit with instructions. Historically, the House has granted the minority the right to offer an amendment right before debate on a bill closes, a procedure known as a motion to recommit with instructions. Both the Democrats and Republicans took advantage of this right by offering amendments that put the majority, especially moderates, in difficult positions. At the beginning of this Congress, the Democrats eliminated the right of the minority to offer instructions—in other words, they could no longer offer these embarrassing amendments. When the Democrats did away with instructions at the beginning of 2021, Majority Leader Steny Hoyer of Maryland, implicitly acknowledged the Democrats’ mischievous use of the tactic, saying, “But we may be in the minority at some point in time. Don’t give it back to us because it is a political game that undermines the integrity of this institution” (Congressional Record; January 4, 2021; H32).

With all due respect to Leader Hoyer, the Republicans should give the motion to recommit back. But knowing that Minority Leader Hoyer will be a man of integrity, the Republicans could certainly expect that he will use the motion to recommit only the most productive way possible.

5. Adopt biennial budgeting. Deviations from the established budget process are now the norm, not deviations. It has been well over two decades since the Congress has adopted all of its spending bills on time and with the bills considered individually. Funding the government with temporary measures after the start of the fiscal year until it can finish the appropriations bills is the norm. Congress can, instead, buy additional time by adopting a two-year budget resolution while still maintaining annual appropriations. Draft the budget blueprint once at the beginning of a Congress, and don’t bother consuming precious Floor time again in the second year of that same Congress. Spend more time on the actual appropriations. Congress often works out two-year spending deals anyways (see the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 or the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019). So why not make the practice official and permanent?

Where We Go From Here

Instituting biennial budgeting would require a change to Federal budget law, meaning the Senate would need to agree to it as well. Other reforms, like requiring a supermajority for a closed rule can be done simply by changing House rules only. Some improvements can come about merely by behavioral change without reforms to the rules (for instance, Members could make greater personal efforts to get to know colleagues of the other party or the majority leadership could commit to open rules).

Implementing many of these reforms would prompt stiff resistance from some—many—Members. Resistance is understandable since there are good objections to both the general principles and specific recommendations. For instance, a committee chair who wants a closed rule to protect their legislation has a point: Why let a Member from outside the committee muck around with a bill that expert Members have prepared? Why open a bill to poison pill amendments? These and other objections are not easily dismissed. Though each idea has its own flaws, the collective force of them overcome their individual weaknesses. The reforms mutually reinforce each other. The more open the process, the better the chance for passing legislation that stands the test of time. Adopting them as a package would leave the House far stronger than if just one or two were adopted.

The House’s strength and vitality comes from its Members and the legislative process they construct. The 118th Congress will see many new Members whose energy and talents will complement these of their more senior colleagues. Together they have a tremendous opportunity to reinvigorate the House by promoting greater civility, strengthening the committee system and promoting dynamic debates on the Floor. Such a House would be an exhilarating place to be a Member. What’s more is that Members and their constituents would be better served by a body where their representative can be their voice on the important issues of our day.

With the ideas offered here, and with changes to Conference and Caucus rules (more on that in a later post), legislators might once again enjoy serving in Congress, and they might govern well while they are at it.